The Most Important Unknown Artist Mladen Stilinović

May 2021 – art magazine Vlna no. 86 “BOOK/LITERATURE”

Review of the exhibition

„MLADEN STILINOVIĆ: IF THEY HAVE NO BREAD LET THEM EAT CAKE“ at Hunt Kastner, Prague

12 December 2020 – 6 February 2021 curated by Branka Stipančić

The Most Important Unknown Artist Mladen Stilinović

At the turn of 2020, the Hunt Kastner gallery in Prague hosted only the second ever Czech solo exhibition of one of the most important conceptual artists from the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, the Croatian Mladen Stilinović (1947–2016). After thirteen years (in 2007 the Mladen Stilinović: I am selling M. Duchamp at the Austrian Forum Gallery under the curatorial supervision of Jiří Ševčík took place) the Czech audience was able to get to know the previously unexhibited works from the nineties and noughties of this Belgrade native as part of a gallery programme that seeks to highlight the work of one artist each year who belongs to the older generation and whose work has left a significant mark on the history of contemporary art and continues to inspire younger generations. At the same time, the conceptual character of the project has made it a part of the gallery presentation of Czech artists such as Dalibor Chatrný or Zorka Ságlová, and it has continued the string of Czech and Slovak projects devoted to conceptual art in recent years (for example, Poetry and Performance at the New Synagogue or the Czech Concept of the 1970s at Fait Gallery). The minimalist installation of works was immediately followed by the performative shouting of the words "Krumpira, krumpira!" ("Potatoes, potatoes!") as soon as one entered the exhibition space, foreshadowing that instead of a record of grocery shopping, the visitor would be treated to an ingenious play with symbols and signs.

The exhibition, which was prepared in collaboration with the Viennese Martin Janda Gallery, was curated by Stilinović's lifelong friend, art historian and critic Branka Stipančić. The programme kicked off with a one-day street event For Marie Antoinette which first took place in 1998 in Zagreb as part of the day-long multimedia manifestation Book and Society – 22% organized by artist and activist Igor Grubic to protest against the 22% tax on books in the newly independent Croatia. Around forty artists joined the performances in the city center and installations in the streets, squares, bookstores and libraries at the time, with Stilinović placing his intervention in Zagreb's Petar Preradović Square (also known as Flower Square). The Žižkov arrangement with loaves of bread and cakes seemed more like a signpost or a path of crumbs worth following from Bořivojova Street to the gallery premises, where it continued through the first room and into the courtyard.

DAILY BREAD

The title of the exhibition, If They Don't Have Bread, Let Them Eat Cakes, reveals the common theme of all the works on display, even though the authorship of the phrase "Qu'ils mangent de la brioche" attributed to Queen Marie Antoinette of France is nowadays questioned. Indeed, such statements, as examples of cynicism and arrogance of power, eventually lead to rebellion, whether for the Great French or for Croatian independence. The never-ending balancing of power and powerlessness in society has become a major subject of investigation for Stilinović since the late 1970s. The very first object on display, On the Swing (1998), a custard cake (“kremšnita'') laid on a simple swing made of jute strings, symptomatically depicts the artist's way of working. The emotional and symbolic significance of everyday objects is contrasted with the power thematized in the contexts of ideology, politics and the art world. This built-up tension is then often lightened by subversive aspects of humor, irony, cynicism, paradox and exaggeration.

The work with language and sign systems in general is characteristic of Stilinović. The adjacent and oldest work in the exhibition, Poor People Law (1993), focuses on proverbs concerning the redistribution of rights, power and justice. Thus, painted tin plates are displayed on a gray field, on which black-and-white pie-cuts with English folk wisdom slogans such as "Every Land Has Its Own Law" or "New Lords New Laws" appear, and sweet cakes supported by black shelves. Though playful in its own way, this work exposes the corruption of ideological talk in everyday language as the basis of human existence. The motif of food appears in Stilinović's work at the same time as the exploration of power, and although it is abundant in the exhibition, it points to the opposite – the poverty and scarcity inherent in the ordinary population and its excess in the hands of the powerful. On the occasion of the exhibition Exploitation of the Dead in Zagreb in 1988, Stilinović even threw the pastry on the canvas.

References to the emptiness of avant-garde art appear in Exploitation of the Dead (1984–1990), which was exhibited in Kassel in 2007 at Documenta 12, as well as in The Law of the Poor – Stilinović, who himself never went through an art academy or other art-oriented higher school education, did not essentially work with large-scale painting, but rather used the aforementioned everyday objects in socio-economic and political contexts. These neo-avant-garde gestures in the form of new media, conceptual or post-conceptual art and performative practices often exhibited or held in public spaces or, conversely, spaces practiced by artists in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since the 1960s tend to be grouped under the heading of "new art practice" (Nova umjetnička praksa). The title is usually derived from the exhibition New Art Practice 1966–1978, which took place in 1978 at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb under the curatorial supervision of Marijan Susovski and concentrated on works that departed from the traditional understanding of artistic artifacts. Works of this type emphasized collective action, the ephemerality of gestures, public participation, or operations with language and images used (or rather abused) by state authorities and the media. In addition to artists such as Goran Trbuljak and Sanja Iveković, the Group of Six Artists (Grupa šestorice autora) was also exhibited, including Stilinović (and with him Vlado Martek, Željko Jerman, Boris Demur, his brother Sven Stilinović and Fedor Vučemilović).

ONE LETTER AT A TIME

The intervention of the loaves of bread with cakes on the floor had its permanent continuation in the installation For Marie Antoinette '68 (2008) in the back room of the gallery, where the objects were placed on a table along with paving stones, which often become a weapon in the hands of a frenzied crowd. The main and largest room of the gallery was occupied by a corridor made up of forty black and white photographs with forty newspaper clippings from 2001 pasted on their reverse side. Photography as a medium in Bag-People (2001; exhibited, for example, at the 15th Biennale of Sydney in 2006) functions more as a mere documentary record of anonymous people returning from a local flea market with goods they purchased there, in dialogue with global events as presented by the media. For Stilinović, the newspaper was a foundational material that he often used to reorganize – to expose the practices by which the media structure information and construct truth. The artist's experience of markets and public street life was already present in another artwork, Geometry of Time (1993). In this installation, Stilinović arranged his works on individually laid newspaper pages on the floor, as vendors in markets do with their goods. The use of cardboard and newspaper clippings is finally evident in Circle without Foreign Exchance (2015). However, the artist's copying of these gestures is not aestheticising, as one might expect. Rather, it is a political kind of communication. More specifically than the other works on display, People with Bags points to the consequences of the Croatian War of Independence, the accelerated process of transforming a socialist country into a capitalist state, and the privatization that resulted in the rise of social inequalities that the newly built Croatia was undergoing.

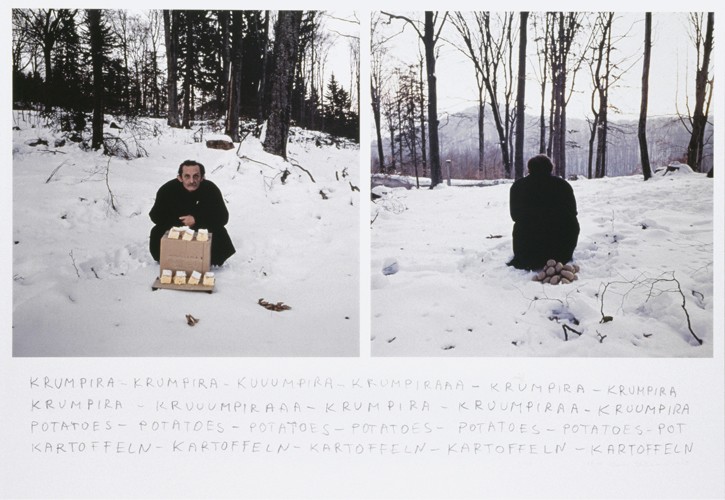

The passage through the corridor not only follows the unpaved path that the society had to go through, but also leads to the video Potatoes, Potatoes (Krumpira, krumpira, 2001), whose main protagonist is the author himself. Set on the edge of a forest in winter, the performance depicts the artist selling cakes instead of the shouted potatoes. Language thus reappears in Stilinović's grasp, following on from his earlier works, when he became interested in zaum language in the 1970s, as a language contaminated, wounded and raped. These are "language games" (according to Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose texts Stilinović knew) that may not yet have revealed their true political or ideological potential. For Stilinović, language was the ideological sign par excellence (in line with the study of Mikhail Bakhtin) and one was therefore constantly trapped in ideology. The plurality of meanings inherent in his works is visible across all the works on display – whether we perceive it as a critique of society or directly of the art market.

The exhibited works are undoubtedly powerful because they are not only related to the history of Yugoslavia and Croatia, but their interpretation is valid across global history, if we look at something as close as our own history (author's note: this applies to Czechia). For Stilinović, ideology was omnipresent and the artist had to play a complex multi-layered game with it. The lightness and incisiveness with which Mladen Stilinović does so in some cases enhances the situation in which neoliberal society now finds itself. Stilinović's work would therefore deserve a more comprehensive exhibition accompanied by a publication that would introduce the Czech and Slovak art community to his work in its entirety, including fundamental works dealing with the decoding of colors, pain, the myth of work, money, laziness or time. However, Stilinović's interest in language has always remained at the center of his main activities, "his celebration of radical spiritual freedom" (in the words of Boris Groys on the artist, e-flux, 2014). In the meantime, the Slovak public can at least look forward to the exhibition planned for autumn at The Julius Koller Society in Bratislava. "For supper I am having Podravka chicken soup, letter by letter, that's it." (Mladen Stilinović, Insulting Anarchy, 2007)